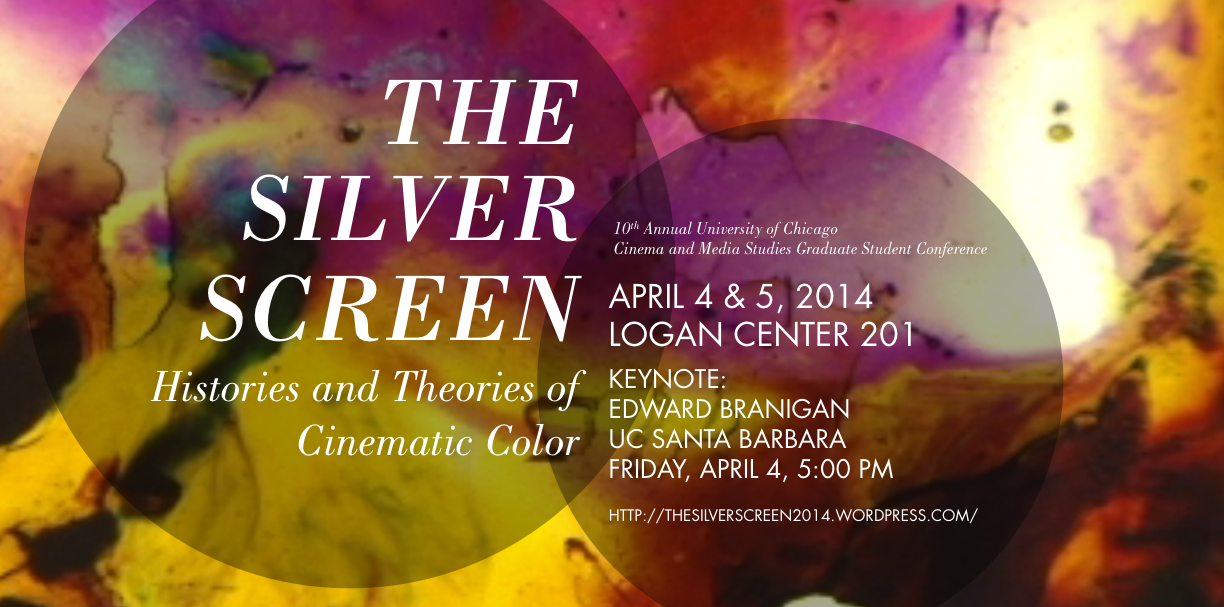

The Silver Screen: Histories and Theories of Cinematic Color

Conference Schedule

The conference schedule is now available!

Call for Papers – Deadline: January 10

The Silver Screen: Theories and Histories of Cinematic Color

The 10th University of Chicago Cinema and Media Studies Graduate Student Conference

April 4th and 5th, 2014

Keynote Speaker: Edward Branigan, Professor of Film and Media Studies at the University of California – Santa Barbara and author of Projecting a Camera: Language-Games in Film Theory (Routledge, 2006), Narrative Comprehension and Film (Routledge, 1992), Point of View in the Cinema: A Theory of Narration and Subjectivity in Classical Film (New York: Mouton, 1984), and Color in Cinema: Language, Memory, Commerce (forthcoming)

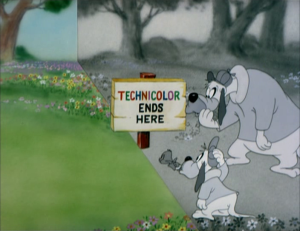

“Imagine a world alive with incomprehensible objects and shimmering with an endless variety of movement,” Stan Brakhage wrote, “and innumerable gradations of color.” This conference seeks to re-imagine the innumerable gradations of color in the history and theory of cinema: from the spectral sensations of light at play in Maxim Gorky’s “Kingdom of Shadows” and Loïe Fuller’s serpentine dances to those of J. J. Abrams’s Star Trek Into Darkness (2013) and its countless lens flares; from the blacks and whites of Italian neorealism to the blacks and whites of Frankenweenie (2012), Tim Burton’s digital 3D stop-motion animated film; from works that explore the synthesis of color and music like Léopold Survage’s studies for Colored Rhythm (1913) and Columbia Pictures’ Color Rhapsodies cartoon series (1934-49) to Mary Ellen Bute’s Color Rhapsody (1951) and Paul Sharits’s Color Sound Frames (1974); from early film processes like Lumière Autochrome and Kinemacolor to color-correction suites like Pandora Pogle and DaVinci Resolve. Like sound, to which it is so often linked synaesthetically, color challenges our basic vocabulary as film scholars. But “are we,” as Roland Barthes asked of the voice, “condemned to the adjective? Are we reduced to the dilemma of either the predicable or the ineffable?” Scott Higgins’s Harnessing the Technicolor Rainbow (University of Texas, 2007), for one, uses the Pantone Color Matching System as a standardized lexicon, while Joshua Yumibe’s Moving Color: Early Film, Mass Culture, Modernism (Rutgers, 2012) offers a historical account of the sensuous and somatic richness of cinematic color.

Yet when films as canonical as Hitchcock’s Vertigo circulate in formats as varied as faded 16mm prints, pan-and-scan VHS tapes, pristine 70mm prints, 360p YouTube clips, and Blu-ray discs, which version do we select as the object of our analysis, and how do we make such a choice without losing sight of the work’s ever-unfolding critical and popular reception? Colors can be “preserved,” “restored,” and “corrected,” but can their cultural meanings? Can we fix color as readily as we can calibrate our television set’s brightness and contrast? After all, color is permanently enmeshed in questions of realism, of spectacle, of film as art and film as industry—questions that this conference regards as catalysts for conversation. Color invites renewed consideration of hitherto understudied participants in film production, such as cinematographers, art directors, special-effects technicians, and costume designers, not to mention the thousands of women responsible for stenciling, tinting, and toning films of the silent era, as well as the women who posed as “China Girls” for film laboratories. It also reminds us of cinema’s relationship to other technologies of reproduction (e.g., xylography, lithography, halftone printing, and xerography) and visual media (e.g., picture postcards, lantern slides, children’s books, television, comic books, and video games), and opens up the discipline of film studies to parallel debates in art history, cognitive science, psychology, comparative literature, musicology, cultural studies, and philosophy.

With these problems in mind, our conference welcomes presentations by graduate students who, like Walter Benjamin, wish to penetrate “the riotous colors of the world of pictures.” Possible topics include (but are by no means limited to):

- analyses of individual films or bodies of films by a single director, cinematographer, or production designer

- histories of technologies, exhibition formats, broadcasting standards, industrial and corporate regulations, craft and technical discourses, etc. (e.g., additive color processes, color film stocks, colorization techniques, NTSC/PAL, computer and video game graphics, digital cameras)

- color’s role in generic construction (e.g., melodrama, science fiction, noir)

- cinematic lighting techniques and art design

- the technical and ideological problems posed by the reproduction of non-”white” skin tones

- visual music and synaesthesia

- color’s affective properties

- color and allegory

- color’s place in classical film theory (e.g., the writings of Eisenstein, Arnheim, Balázs, Bazin)

- the theory and philosophy of color (e.g., Albers, Kandinsky, Wittgenstein, Goethe, Schopenhauer) as applied to cinema

- reappraisals of the historiographical models advanced in Edward Branigan’s “Color and Cinema: Problems in the Writing of History” (1979) (“the adventure of color,” “the technology of color,” “the industrial exploitation of color,” “the ideology of color”)

- color and memory/historicity

- contemporary artistic, avant-garde, and popular appropriations of cinematic color (e.g., Jason Salavon’s The Top 25 Grossing Films of All Time, 2 x 2 (2001) and Emblem series (2003), Les LeVeque’s Red Green Blue Gone with the Wind (2001), Cory Arcangel’s Colors (2005), Julie Buck and Karin Segal’s Girls on Film (2005), the Movie Barcode Tumblr, John LaRue’s “Colorizing Walter White’s Decay” infographic)

- the aesthetics of black-and-white film and video

- the theory and practice of film restoration

- color motifs and narrative structure

- historical trends in color design

Interested graduate students should submit abstracts of 250-300 words (along with institutional/departmental affiliations and current email) to silverscreen2014@gmail.com by January 10, 2014.